Within the educational sphere, July and August tend to mark the beginnings of fresh leadership appointments in both school and central office positions. As fresh faces assume a new leadership role, many are afforded the opportunity to build their own leadership team. In prior years, I was blessed to have an opportunity to sit on new leadership teams, both at the school level and on a Superintendent’s cabinet. In each of those leadership appointments, I walked into the role with some hesitancy about my abilities and how I would share my ideas, opinions, and sometimes reservations about a particular idea initiated by my boss. Perhaps it was imposter syndrome that led me to lead and question with trepidation. Too often I questioned my preparedness for certain roles. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for some women, especially women of Color, to internalize feelings of inadequacy. Academic and author, Julia Chang, recounts her experiences in academia while in a tenured track position at an Ivy League University. Chang stated, “The imposter syndrome causes me to feel precisely this: that I am not one with my skin, as though I had the encasing of one fruit and the flesh of another” (2020, p. 261). Chang described my sentiments precisely. I entered the workplace as a confident Black woman having started my career in Baltimore City Public Schools in the early 1990s, but I would find that my Blackness was too much for others to bear in other spaces. As a result, I tempered a little of myself to belong and get along.

While I began my 28th year in education earlier this month, I must remind myself that I have served as a teacher, assistant principal, principal, assistant superintendent, and superintendent at various points in my career. I pursued the superintendency at the encouragement of a former boss current Superintendent and friend, Dr. Andre D. Spencer. Even with a wealth of experience in various school systems, my inner being was always on guard for self-doubt to seep in. Still, I was pleasantly surprised that on many occasions, my immediate supervisors assured me, through their interactions, affirmations, delegated responsibilities, and a keen interest in my continued growth, that I was hired because they unequivocally believed in me.My input was welcomed, if not sought after, by a handful of supervisors. I recall times when they would never allow a meeting to conclude without the voices of those at the table being heard. In the beginning, I shunned this practice. I was weary of being called on in front of others for fear of saying the wrong thing or simply not knowing what to say. Yet, the spaces these leaders created allowed for conversations to ensue without fear of embarrassment or judgment. Later in my career, I would do my best to embody that same practice of seeking the thoughts and ideas of others. As a former school leader and cabinet official charged with leading, it was rare for me to conclude a meeting without everyone’s voice being heard. For example, prior to moving forward with any systems’ level change, I would pose a very simple question to my direct reports and/or colleagues that asked, “What are the landmines?” Landmines may not have been the best word choice, but the phrase conveyed, “consequential impact”. As I observed the plethora of new leadership appointments shared in the local media and/or on social media platforms this summer, I thought to myself, who will ask, “What are the landmines?” Who will challenge ideas that are not fully fleshed out or simply flawed?

Well, there is no need for me to withhold my thoughts from you any longer. In considering the political and vitriol atmosphere plaguing schools, school board meetings, and other venues where school personnel gather, I rely on the good book, the Bible, to share my lingering thoughts. Specifically, I am drawn to the book of Esther as I try to frame my thinking around leadership. In my opinion, the Book of Esther is one chunk full of the essential elements for making a great story. There is the protagonist and antagonist, exhilarating suspense, conflict, and finally, a resolution. For those who are unfamiliar with the Book of Esther, I will provide a brief synopsis and hope that this summary, albeit brief, compels you to dust off your bible, find Esther, and get to reading. Esther, raised by her uncle Mordecai, is a Jewish woman from the Persian diaspora. King Ahasuerus, at the first sighting of Esther, becomes enamored with her beauty. Long story short, King Ahasuerus makes Esther his wife. According to some bible scholars, in the time leading up to the King and Esther’s wedding and during the early part of their marriage, Esther did not reveal her Jewish heritage to her husband, the King. Mordecai made this request of Esther for fear that the King would abandon all thoughts of marriage to Esther. If you’re wondering why, well now is a good time to go get that bible. There is another character in the Book of Esther, Haman. Haman, an advisor to King Ahasuerus, is promoted above all the king’s officials and the king demands that everyone bow down to Haman. Mordecai refused to kneel and bow down. This refusal, in an act of defiance, is where things get interesting and where I draw parallels between the book of Esther and present-day leadership.

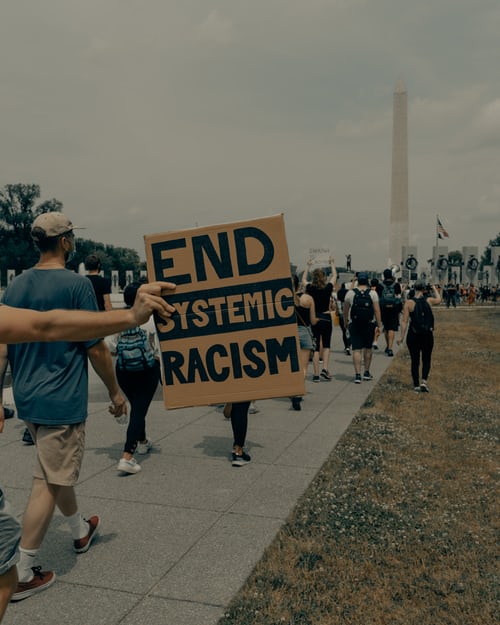

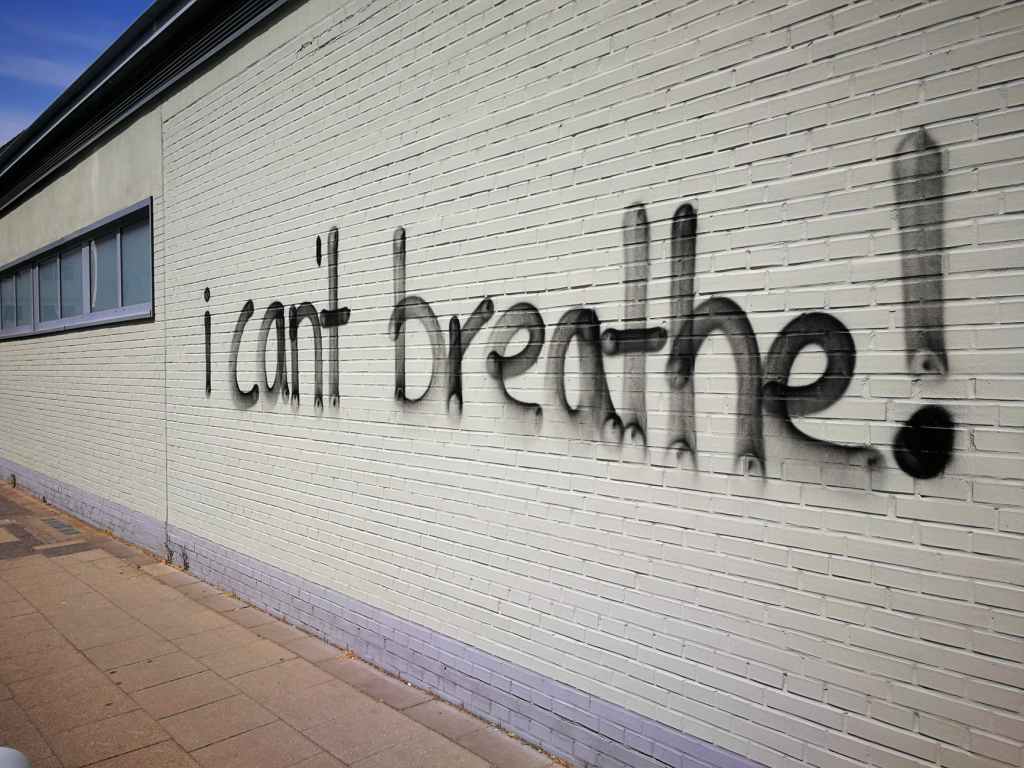

As I shared in my opening, the summer months typically mark the beginning of fresh starts for school and central office leaders. School principals and superintendents are sometimes able to appoint new leadership to their inner circle whether as an assistant principal in schools or chief of staff, assistant superintendent, or similar positions at the Cabinet level. If you are new to your position, you may not feel as inclined nor encouraged to voice your thoughts and opinions especially when they may be in opposition to the views of your supervisor and/or colleagues. If, however, you were selected to serve in a leadership position, then it is critically important that you muster the courage to speak up and out. I recognize, however, that sharing your thoughts and ideas is easier said than done especially when speaking, uninvited, can come with consequences-some immediate and tangible, while others slow and career hazardous. But bell hooks (2004) reminded us on many occasions that our voice is not just a matter of self-preservation, but our voice can serve as a movement to trample the systems of oppression. So, why stay quiet? For whose comfort are we considering? Who is harmed by our silence?

When Mordecai refused to show deference to Haman, Haman was enraged. Haman’s anger further fueled his hatred of people of Jewish descent and led him to devise a plot to destroy all Jews. Mordecai learned of Haman’s plot and went to Esther with a plea that she intercede on behalf of her people to the king. Esther is hesitant to go to the king because, according to the customs and laws during that time, she is keenly aware that approaching the king without him beckoning for her can lead to her death. Mordecai learns of Esther’s hesitancy and sends a powerful message back to Esther, “Do not think that because you are in the king’s house that you alone of all the Jews will escape. For if you remain silent at this time, relief and deliverance for the Jews will arise from another place, but you and your father’s family will perish. And who knows but that you have come to your royal position for such a time as this?” (New International Version, 2011, Esther 4:13-14)

When scouring the internet and electronic library databases using keywords like, “Mordecai”, “Esther”, “courage”, and “leadership”, the findings seem to depict Esther as the heroine. I, however, want to offer a different perspective, one that illuminates the courage of Mordecai. Look at Mordecai’s position; he is not the king nor is he the king’s official. Yet, Mordecai uses his ‘given’ position as a means of influence and thus, I draw parallels to your position and mine. There are at least three types of organizational power: role power, relationship power, and expertise power. Of the three types of power, relationship power is often underestimated. Relationship power is our ability to forge relationships with others regardless of where one falls on an organizational chart. Even John Maxwell affirms this position in his book, The 360 Degree Leader. Specifically, Maxwell posits, “You can lead others from anywhere in an organization” (2011, p.7). While Mordecai had a relationship with his niece, he could have remained quiet, but he did not. Mordecai used his relationship and positionality to wield some influence over the “role” power his niece held.

After Esther, Mordecai, and their people engaged in three days of fasting and praying, Esther was petitioned by the king who wanted to know why she was in such distress. Esther shared with the king the plot Haman devised to annihilate the Jewish people. In the end, Haman was impaled on the pole that he had set up for Mordecai. The book of Esther has ten chapters, so many details are withheld here. The moral of this story is to illustrate the power of one voice, a voice that refused to be silenced. If you believe the parallels I am attempting to make between Mordecai, Esther, and those of us in leadership positions are hyperbolic, then do nothing. But, if you visualize the faces of individual students, countless families, and even staff members who are harmed by our unwillingness and/or fear of speaking up, then I implore you to be silent no more.

The journey of leadership is often a complex and nuanced one, shaped by our personal experiences, societal dynamics, and the courage to overcome self-doubt. As we navigate the educational arena, marked by transitions and fresh beginnings in leadership positions, it is imperative to reflect upon the lessons from history that can guide us in these roles. The parallels drawn from the Book of Esther, I hope, offer profound insights into the essence of leadership. Esther’s courage to step forward despite the risks she faced resonates with the challenges many leaders encounter when speaking out against the status quo. Likewise, Mordecai’s courage and unwavering determination to make his voice heard, even from a position of relative powerlessness, underscores the influence that relationships and the willingness to speak up can wield in effecting change. Leadership should not be confined to titles or positions, but rather should emerge from the disposition to inspire and influence others, regardless of where one sits on the organizational hierarchy. The power of relationship, expertise, and the willingness to challenge flawed ideas or systems can shape the course of leadership trajectories, ultimately contributing to the transformation of educational institutions and beyond.

Finally, let us draw courage from the stories of those who dared to speak up, who challenged the norm, and who used their positions of influence to create something beautiful for those we’ve been charged to serve. In doing so, we can pave the way for a more inclusive, thoughtful, and impactful educational sphere that empowers leaders to rise above self-doubt and champion positive transformation. As we step into new leadership roles or continue to grow in our current ones, let us heed the wisdom of author and activist, Audre Lorde who said, “It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish” (2017, p. 91).

References

Change, J. H. (2020). Spectacular Bodies. In Y. F. Niemann G. G. yMuhs & C. G. Gonzalez (Eds.), Presumed Incompetent II-Race, Class, Power, and Resistance of Women in Academia. Utah State University Press.

hooks, b. (2004). Rock my Soul-Black People and Self-Esteem. Simon & Schuster.

Lorde, A. (2017). Your Silence Will Not Protect You. Silver Press.

Maxwell, John C. (2005). The 360-degree leader: developing your influence from anywhere in the organization. California: Nelson Business.

New International Version. (2011). BibleGateway.com http://biblegateway.com/versons/ New- International–Version-NIV